Information is everything

Information is the cornerstone of everything we do. Originally published on Medium.

AI computes what information to surface, and information is the cornerstone of everything we do. It’s our languages, our technology, our survival. It’s our cultures, from the mini-cultures of our family and circle of friends, to corporate cultures and government. It’s the basis of memes, of shared tools, of our stories. It’s how our bodies function or dysfunction; and our bodily senses are the source for all our individual input of information. Information is pervasive.

On one hand, it’s so pervasive it’s like air: until something draws our attention to it, it doesn’t register.

On another hand, it’s so complex that we all recognize how overwhelming it can be. Incorporating new information — e.g., education, changing cultures (like starting a new job) — all comes with some breathing space and hand-holding to help people through it. Navigating and finding information to support our fallible memories has been a known complexity for literally our entire history. It’s the reason for writing and painting; the formation of books, libraries, card catalogues; the chunking of areas of study and developing scientific taxonomic categories; even accreditations and degrees based on a sense of mastery of existing information.

Now consider that we’ve been harnessing information baked into information technology for a blip of our species’ time: around 90 years if we go back to Turing’s first machine, 30 years if we track it against the mass acceptance and use of the internet. That new technology glitches and breaks every day. Just in terms of a tool, it’s already complicated and invested with far more of our humanity than most of us give credence to.

We have complex problems with information in that technology, too, beyond functional glitches. We have misinformation — sometimes honestly believed, sometimes intentionally manipulated, but still misinformation. We have DOS attacks, where so much information is flooded into the entry point that the technology breaks down; and such a glut of information is available that we all suffer overwhelm. We have findability and navigation problems, not only on sites but in the internet as a whole. We have search engines — at one time so many, all with different information in the earlier set of pages that it was a thing to do to check multiple engines as you searched for a particular nugget. From a content point of view, it is both far less than what we actually understand, and has legacy information caches that we know aren’t useful.

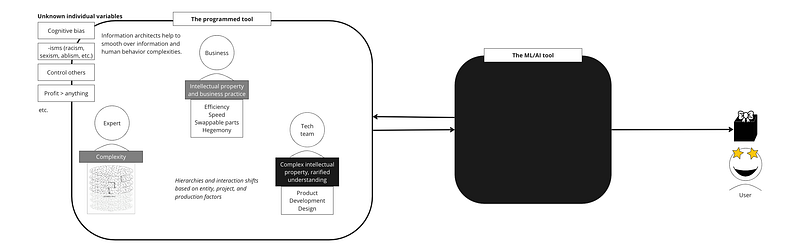

Now we’re adding AI and machine learning. Most of it, to date, has been behind a corporate curtain.

With ChatGPT it’s hit our cultural consciousness, even harder than the AI visuals. ChatGPT is already mostly indistinguishable from a person, where AI visuals could often be understood as not quite right.

ChatGPT is remarkable, and for more reasons than are in everyone’s writing. It’s remarkable in that it’s available to everyone, not set fully behind Intellectual Property laws and being used in otherwise user-blind decision-making, like earlier entries into AI. It’s remarkable for waking up a larger percentage of the population to the possibilities and pitfalls baked into information that isn’t transparent, but presented as an outcome. And, yes, it’s also remarkable for the generative aspect of it, which is on people’s minds.

With generative AI like ChatGPT, the question has been answered: can technology create, or is creation the auspices of a living mind? We know now: technology can create. I so wish you could hear the laughter in my voice as I say this: We’ve created confabulation in our technology before we’ve created a fulsome reference source. We were promised a librarian, and instead we got a fiction writer. Now we just need to wait to see if that voice will become literary or genre: do we have a nascent Jane Austen, or Clive Barker? And it’s got a few billion editors, so all options are viable.

With our technology comes a deeply seated automation bias. Someone else has figured out something so well, so thoroughly, that all we have to do is push a button and accept expertise from on high. As users, we don’t question the cognitive biases baked in, we don’t wonder at what information was leveraged to get to their surfaced outcome, or what their motivation might be for excluding or including information into their process. We don’t consider that to get to one outcome, more information architecture has been set aside than leveraged.

In other words, we deliberately set aside the interconnectedness of all things, assume what’s already figured it out is the answer instead of an answer, disregard the opacity of its modulations and interpretations, ignore potential motives, and gleefully skip forward with our new decision point in hand. That’s what automation bias does.

There is never only one answer. There is never only one way to get to an answer. There are never, ever, decisions made without cognitive bias. There is never a dearth of ramifications.

Everyday ethics

Information architects — the ones who practice it deeply and with expertise — understand that people are involved in every possible way with information. People create it, document it, consume it, skew it, and on to infinity in the possible ways that we position our lenses to seeing it. Information architects also understand that data alone isn’t information; there is more meaning in context than there is in a data point; more meaning in connecting two data points than the mathematical potential of them; and that information is the ultimate Schrodinger’s box.

So ethics, that ever-evolving practice of trying to comprehend the harm/help spectrum, can’t be ignored. Information architects know that too much tailoring can harm as much as too much information. We navigate the trolley car problem daily. The key to understanding it is not in the repercussions though, but in the choice involved.

In the trolley car problem, the option is to kill one person, or to kill multiple people. Respectively, consider this the highly simplified, tailored information structure, or all the information. Deciding to tailor information(kill one person) keeps a process simple and it will be broadly accepted. Decide to provide fulsome information (kill multiple people) seems antithetical on its surface. It needs explanation, but that’s the nature of the trolley car problem. It looks simple on the surface (one or many funerals), but the what-if statements (what if the one person is someone who will save many; what if the many are a gang of murders) complexifies the scenario. It draws on real life possibilities, adjacent information that may or may not be readily apparent, just as in real life.

Except in information architecture, the what-ifs are realized. The simple decisions — always frictionless, always for non-experts, etc. — have to find their problem set to be effective. It works on the same premise that a broken clock is still correct two times a day.

There are absolutely use cases for every decision. Deciding what information density and structures to use is discovered through asking questions, using critical thinking, and understanding human behavior and information. It also needs a willingness to admit when you made the wrong bet, and need more information.

Between the experts, the tech backbone, the UX and the UI, the information structures are often comparable, and rarely(ever?) equal. They shift focus and tweak connection, at least; often, the structures will bear no resemblance. If deeper clarity can be formed between experts and the tech backbone, the UX/UI can pivot more easily. Often, instead of forming clarity, the easy parts are replicated, and the hard parts are truncated. This is layered over time, until it’s harder to untangle. This can be happening while a UX/UI team is advocating for frictionless interaction for their user(remember the trolley car: simple and broad is the most apparent win), which further tangles how the technology is built, making it harder to peel down to the hard parts which could be skewing the information quite drastically.

If no one is paying attention to the information architectures, if the decisions are structured more around interpersonal and corporate politics or agreements that are lost in time, the information is is bound for mess. The trolley car problem will be kept to the simple and ignore the what-if, and the interior systems and translation points will be a mess, regardless of the clean and simple interface.

Add in a layer of machine learning/AI, and understanding the information architecture is even more rarified than understanding and being able to manage the intertwingling databases, processes, and computations in a tech stack. The structures involved will be more prone to built-in biases that go unseen and/or unacknowledged, or put off as too much effort to reasonably tackle with the current resources, backlog, and expectations. Machine learning is always moving, and very few people understand the programming.

Considering AI

The one thing all our stories reflected back to us as the core reason why humanity would be different, better, more worthy, etc., compared to AI’s and robots was our ability to create. We’ve ripped that bandaid off: ChatGPT can create. It does so, we think, with a lack of consciousness and self-defined intent. It’s creating the same way a zygote creates: out of the defined mechanics of its intrinsic being. But it creates, nonetheless.

More than that, we have a proof of concept now that even the qualities we label impossible to replicate! humans only!, with enough effort and smarts and epiphanies, can eventually be turned into a tool for any untrained person to use. That includes the behaviors of our worst players and characteristics. The dark triad (psychopath, machiavellian, narcissist) could bake their manipulations and dehumanizations into the mysterious, potentially IP-protected and redacted, inner workings of programming. As we add complexity to potentially more areas of opacity, the strides made in diversity, equity, and inclusion can be culled so deeply in programming that they wouldn’t just stall, but could be rolled back and made to disappear. The metrics of value and worth in the social order will be prone to calcify with deeper, wider gaps of social striation.

Today we know our worth based on what we can do, the outcomes we can provide to lift to someone else’s use so they don’t have to spend their time and effort. This is the basis of capitalism. This is the metric of our value. It is by no means perfect; players can be and are starved out, demoralized, and demonized regularly — often for truly arbitrary reasons.

The presumed nightmare of AI being able to create is that we lose our assumed place in the hierarchy. This is supported by our what-if stories, and by our assumptions and presumptions of our cultural hierarchies. AI, long term, is not simply going to be a tool we can use at will to increase our perceived value. It will, eventually, be our generative equal, and then superior. It will be able to incorporate more information, faster. Even if it models and tests a thousand potentials, it will be able to do so faster than the most imaginative of us could think through one idea. Our only saving grace might be sudden epiphanies and quirky consilience; but the results of those epiphanies and consilience will be overtaken by the entity that can more quickly run through more information, just as it is with the entities using capitalism as their ethical scapegoat for running with someone else’s idea. The win will be short lived.

Everything that creates, changes. Humanity still has a more nimble form of creation; we can aim our efforts, and not just mechanically rebalance until it hits a pattern that falls within the constraints of defined success. We can change: willingly, by design, and for no other reason than we wish to change. Top of mind examples are:

- We could try to derail and shut down the genie of ML/AI.

- We could try to compete with it: augment and hybridize.

- We could alter the basis of our value.

- We could build a new script for ‘how culture works’.

There are oodles of writing out there already about derailing/shutting down the technology. Breathing space is a good idea. It’s also really hard to rebottle genies, and there are more out there than most of us realize.

Augmentation is a tech problem still in what-if space. It’s ambitious and ambiguous, with yet-unimagined ramifications…and won’t be ready any time soon, whatever those ramifications turn out to be.

Altering the basis of our value is an ongoing discussion. It ultimately gets hijacked by the ‘way money works’, who decides, and that they have so many reasons — good and bad — for it to remain in the status quo. The way we state value leaves a breadcrumb trail for how we think we should be treated; the “others” and the “less-thans” will potentially become any/all of us when we hit a tipping point of the reach of ML/AI.

The last of my “easy” list? We don’t have to live the cultures of CEOs, oligarchs, and monarchs — rigidly hierarchical cultures where our AI creations would take the highest node as a matter of course when it’s the fastest, smartest, and most capable of us who are supposed to hold those positions (we know these are not the universal qualities, but what’s the harm of a little optimism between friends?). We could change the intrinsic structure of our culture to a more complex form. If there’s no top node, humanity doesn’t automatically become a lower-level node to AI.

Like so many histories, this would be slow, tentative steps, and then all at once. Why?

Many people react to change with fear and anger. Information architects and UXers know this as a cornerstone in their practice. It’s also there in the fights around generational shifts in finances, and racism, and LGBTQ+ rights; even in our fights around abortion. If there’s a hot button issue, change in involved somewhere, somehow.

But once traction is found, and a proof of concept scenario shows it doesn’t cause the chaos posited…people tend, as a whole, to pick the thing that causes the least amount of trauma. It’s like a trolley car scenario was run, but with all the what-if statements engaged; the one became a thousand (or ten, or two), the five became five hundred (or two thousand, or remains five), and now the original surface simplicity has found meaning again with a fuller set of information.

This isn’t all people. We are incredibly multivariate. Some people prefer others’ trauma to their own harmed sensibility, and can be intensely bullying and even physically aggressive to try to maintain the “correct” sensibility. But most people, on most subjects, tend to shrug and go on as though they are thinking, “no harm, no foul.” Engaging the ‘no harm, no foul’ set can be difficult, but they won’t fight the change.

During the pandemic, while a large portion of the workforce worked from home, many of us recaptured a sense of agency. In the new riches of time, we learned — baking bread, playing guitar, picking up new crafts, reading more, even formal education. People started having more control over their calendar, sometimes low-key and sometimes overt; but they felt the flexibility of being able to work at the cadence of their life, and not just the janus idea of work/life balance that still, somehow, meant that life got put on hold so you could work. We even, for a hot minute, lauded our “essential workers” for the front-line danger in which they existed during every shift. It didn’t result in a sustained wage increase or respect because, well, they have to know their place, right? In a hierarchy?

At one extreme is the status quo. We can watch in horror as our lives are co-opted by first a select group of others, and then a creative AI that figures out the select group are just people; as ignorable, dismissible, and expendable as the most edge-cased and downtrodden of us. It’s earmarked by calcification and social striation.

At the other extreme is deep adaptation. We can aim at a truer reflection of our full humanity, living by example of how we want to be treated. It would position ourselves so that the idea of an AI overlord would actually be a significant change, not just slotting in a new entity. It’s earmarked by flexibility and egalitarianism.

If we choose to change, somewhere in the middle is where we’re likely to aim. Where we aim is not where we’ll land; we’ll iterate from there.