Getting to binary isn't...binary

Current information technology hardware functions on a binary substrate of ones and zeros translated to electric gates (highly simplified!!), with lots of programming layers between that substrate and the code. That code controlling the hardware is something most of us don't understand. Over that, we're layering in systems architecture, data bases, process, etc., to get all the code to hang together and function. Finally, we get to the code that layers in interfaces, which have been designed and maintained with a variable mixture of information architecture, experience signals to help people orient, content, and visual language that manage and inflect the substrates, all working together to aim at "intuitive". But all, in the end, cascading down to the binary at the heart of computer hardware.

Binaries are more straightforward on computers than non-binaries, continuously and robustly translated down to the hardware. That doesn't mean binaries are conceptually straightforward. 😉

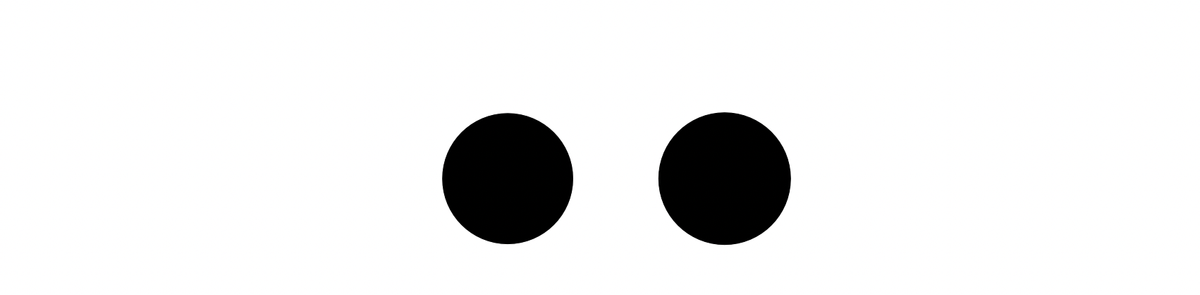

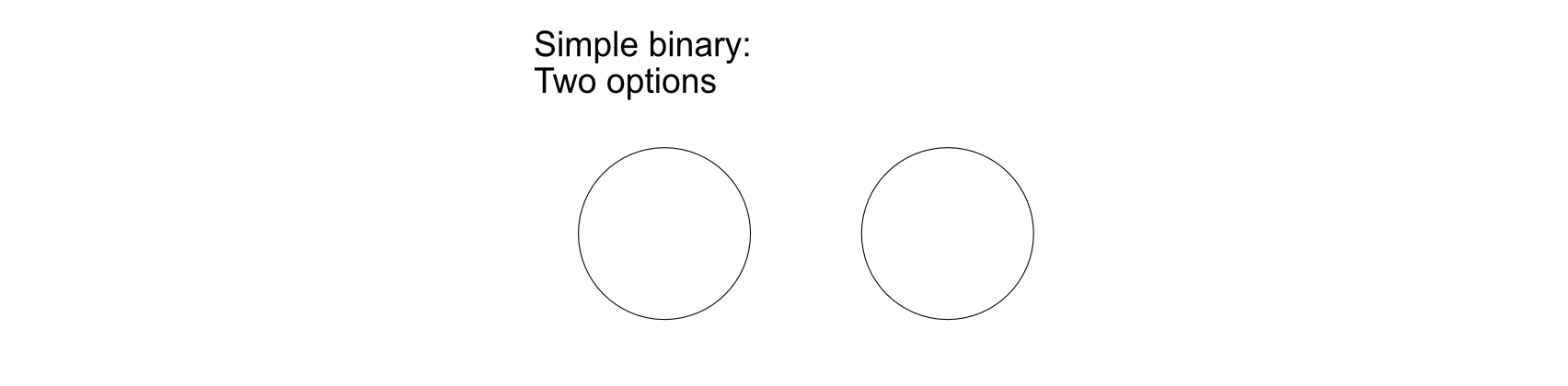

Most people see a binary as two positive forms.

Your option for lunch is a cinnamon roll, or a yogurt.

The label is clear, the options equally clear. The binary governance says it has to be one or the other. Choose one, and it's now your everything.

When decisions are that simple and limited, binaries work. But we don't have to look far to see when the construction of binaries start breaking down: as a model in our decisions. To be fair: binary decision making is not the norm, so much so that I did not include it in my go-to model.

Many of our everyday decisions can be translated into a no-go/go. It's a binary no/yes, with the forward motion being the decision, and anything lacking forward motion a non-decision translated to an emphatic "no" for the sake of the binary.

You want a cinnamon roll: no-go/go.

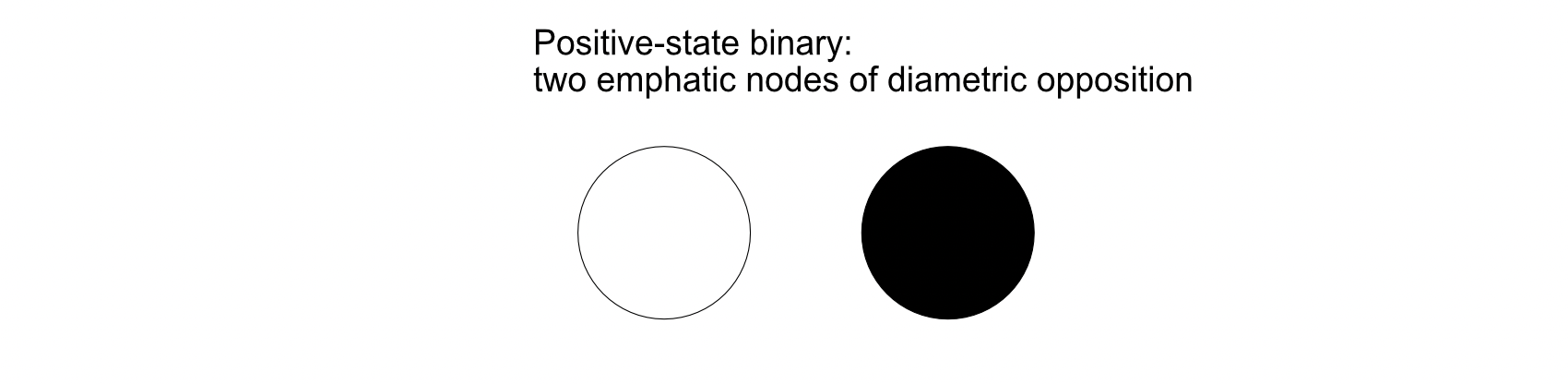

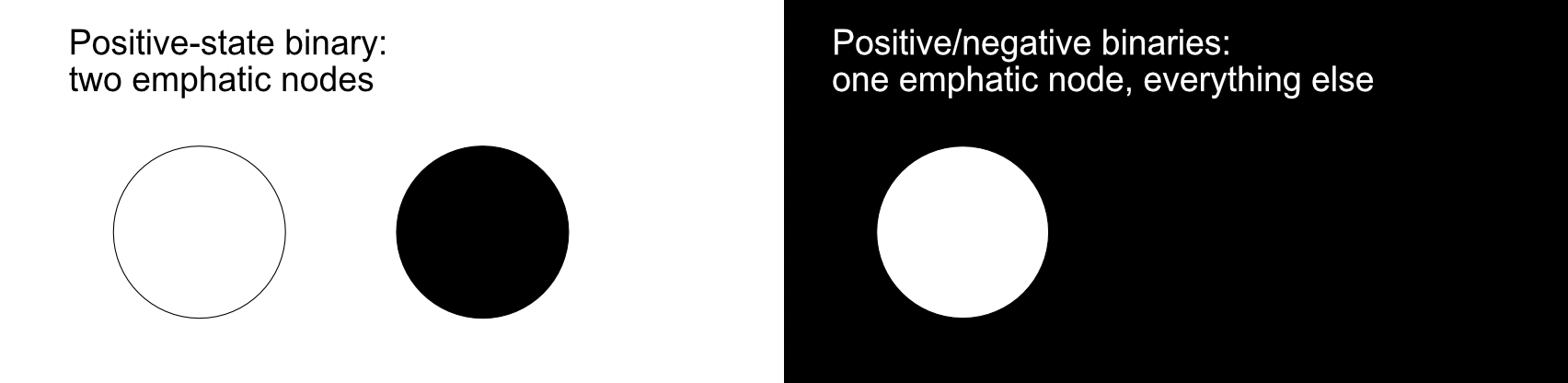

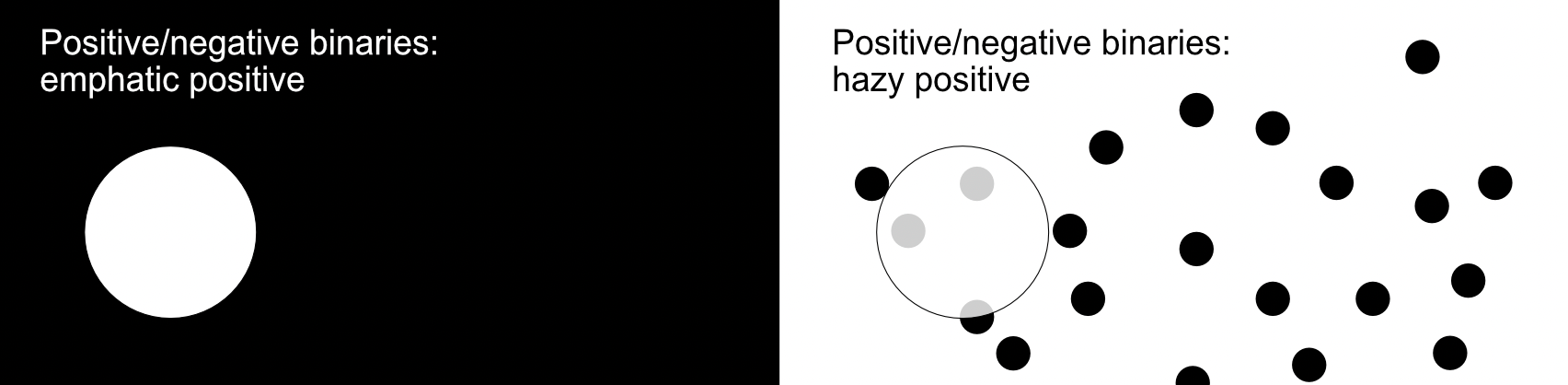

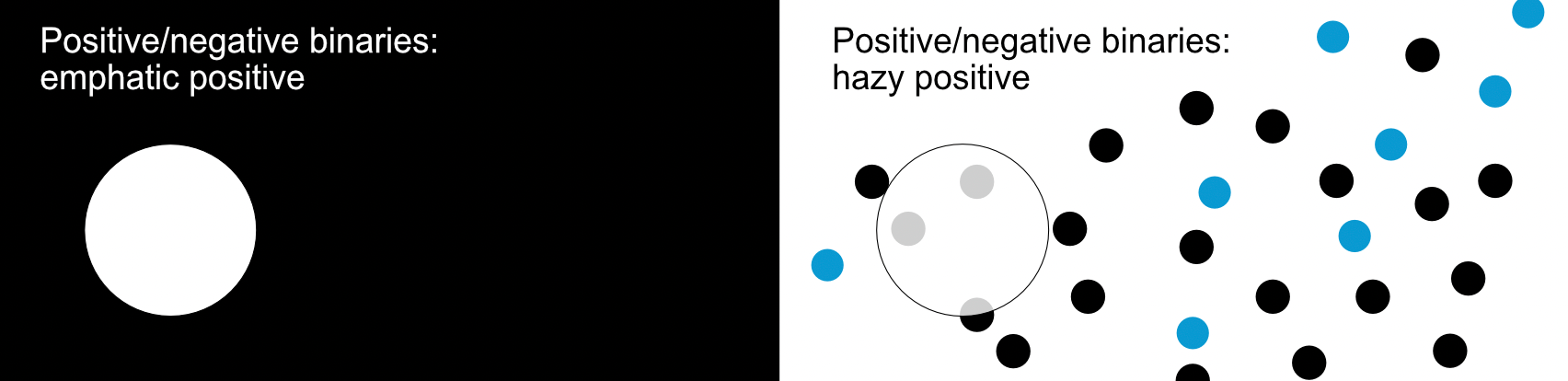

Something we don't often think about (even in IT) is that we are often talking about constructs that boil down to no/yes. "Yes" counts, and "no" is everything that leads to a non-yes. All the ways that make a decision a no-go are swept up in a fuzzy glob of nearly-non-meaning.

It's not two positive-form binaries, but a single positive-form binary with a negative space that is every other possibility. In our decision making, until the moment a decision is made, it was a fuzzy state of no-go, from a non-potential to a strong probability.

You want a cinnamon roll. There's reasons not to have it; you're in a no-go state. But, at one point you decided it was happening anyway: go.

Note how weird it feels to say no-go/go. I think it's because, in that order (no-go/go, no/yes, wrong/right), it prioritizes the fuzzy state of everything-that-isn't. That fuzzy state is a multitude: every possible reason other than the final positive form. It is, in actuality, non-binary. It's only in opposition to an emphatic positive that the entirety of all the reasons why can be relegated to a category of no-go/no/wrong.

You want a cinnamon roll. There's twenty reasons not to have it. But, at one point you decided it was happening: go.

Decision-making modeled as a binary is still more complicated, because there's prioritization going on and a push-pull of reasons. It's not just the twenty reasons you shouldn't have a cinnamon roll, but another eight that suggest having a cinnamon roll is a really good idea.

You want a cinnamon roll. There's twenty reasons not to have it, with yes probabilities also weighing in (so yummy, just 2 hours to make from scratch, 5 minute walk away...). But, at one point you decided it was happening: go.

When we're talking about binaries, it doesn't matter whether the decision is formed around the ideas that would push towards no or the ones that pull towards yes. All the potential states are effectively globbed into the no-go fuzz.

When we focus on the binary aspect of decision making, but admit to the fuzziness of the pre-states, we often create stories around it. Right or wrong (see how easy and aligned that feels?), the story calms us that the decision was well-formed. It could have tipped over for something arbitrary (smelled cinnamon), or even be despite something that we know causes broader damage (you're diabetic, celiac, it's the last cinnamon in existence, etc., but...). If it's too much to keep all the push/pull in mind, we re-simplify it back to an emphatic positive.

You had a cinnamon roll.

There's also a cognitive trick that happens if someone's approach is really tightly focused on binary: what happened is the only thing that matters. Because they are still alive, it must have been the right thing to do. Because everything else has been simplified down to a binary-made-from-fuzzy-potentiality, everything else was lumped together. Even if yogurt could have kept you equally alive, it wasn't the choice made so it gets lumped into the no-go, which is synonymous with 'wrong'.

Also meaning that they could start thinking they only make good decisions.

It gets complicated from there. Thank goodness human cognition has a multiplicity of models to draw from.

The positive-form yes is also what a computer is able to log. Regardless of how complex the reality might be, it can only log what's been defined. Back to the choice about cinnamon roll or yogurt that we started with: on a computer, it's really two positive-form binaries (cinnamon roll|everything-not, yogurt|everything-not) with a binary function between them governing an either-or. It doesn't acknowledge anything else exists.